Although its literal translation into English is “counting days,” the Maya concept of xook k’iin is not necessarily a method or methodological guide, but a culture—or a part of it—that is observable, experimental, or experiential, since it is an every day, night, afternoon, or morning occurrence which is harmoniously woven into nature. It is like a house where each inhabitant responds to the natural stimuli that arise from the same indivisible fabric of life. The faces, colors, sounds, sizes, shapes, conditions, times, distances, and movements that take place in this Maya house, or territory, form the harmony of a script read aloud among women, children, men, animals, birds, clouds, plants, earth, water, rocks, caves, insects, flowers, and all of the inhabitants of this casa grande (great house) nourished by time, by the iik’ (wind), and by the Yuumtsil1. This way of experiencing or understanding Maya culture is essentially a campesino’s reading of the occurrences within his house, shaped by the territory he inhabits, to form part of life’s other creators. The child learns to interpret the weather, the cold and heat, the roads and paths, the rain and drought, among other texts that parents have left to their children. The parents are responsible for identifying in these texts the best conditions for planting and harvesting, in order to protect the milpa2 and the best time for hunting. The secret to being a good reader of these scripts is to have contact with them, as do children from the time they are in the womb.

The epistemology that emerges from an experience woven with the knowledge of the grandparents is a specific way of understanding reality through the environment constituted by the forest, land, water, milpa, and honey, among other fundamental elements of existence, and to experience the world in which the Maya community consolidates an identity shattered by conquest and colonization. Resistance, as a decisive option for life, reweaves the fabric by taking refuge in the milpa where the familiar bond with the Yuumtsil is strengthened. In the house of the Maya, which we may also call the peninsular territory, the sounds and images that spring from the bosom of Mother Earth are perceived by children and women, and mainly by the community elders, as messages, convocations, warnings, denunciations, prophecies, supplications, announcements, voices, and faces of the Yuumtsil. This relationship does not occur automatically in persons because they are part of the population, it is due to a process of coexistence, of attentive listening, of permanent observation, of contact with the inhabitants of the casa grande which is initiated when the mother begins to decipher to the child in her womb the hermeneutic key of an onomatopoeic epistemology that comprises the Maya heart—that is, its identity as a source of language.

The xook k’iin is not a form of knowledge that is frozen, fixed, linear, or romantic. On the contrary, it is dialectical, since the Yuumtsil apply, change, or combine colors to landscapes, images, waters, and the sky. They do the same with sounds, making certain types of harmonic arrangements with flats and sharps and their respective tempos, like the good musicians they are. Our task as women and men of the milpa is to find the lines and curves of images and landscapes, in this way allowing sensitivity to read the score that indicates the times and the best conditions for family and community organization, festivities, spirituality, and good health. Although the xook k’iin encompasses the entire life of the community within time and space, it is eminently agricultural. It is a form of knowledge that materializes in the implementation of the milpa, from the moment an area of forest is prepared for planting, since all the inhabitants of the house—that is, the territory—are impacted by energy (“luck” or “charge”). Trees, animals, insects, cold, heat, the weather, the moon, and so on, everything has a certain energy depending on the day. Thus the campesina who performs a good hermeneutic reading of her environment can decide, for example, which type of maize seed should be sown, the appropriate month or week, the ideal position of the moon, the intensity of the dew, or the currents of wind, among many other signs and signals, especially if the yuum lubcháak (“rainy season”) is about to arrive. The Maya ritual, or what we call u meeyjul Yuum iik’, is necessarily linked to an accurate reading of the weather perceived through the stimuli of animals, birds, and insects, and its fundamental purpose is to ensure health to the house/territory and its inhabitants. The mother/father, creator of wind, energy, mood, and emotions is Yuum iik’, the nucleus of life and source of health. The Aj Meen3 possess a broad knowledge of the Yuum iik’, with whom a family and work relationship is established, and permanent coexistence.

Haizel de la Cruz: "Hojas del Territorio"

Haizel de la Cruz: "Hojas del Territorio"

All Maya rites in the Yucatán Peninsula are celebrations for the Yuum iik’, with the Yuum iik’, and in the Yuum iik’. The mediator is the Aj Meen, organized collaboratively with the family, community, or convening region. Although most of the rites are agricultural rites divided into three parts, there are others that are not strictly agricultural, such as the jéets méek’, the k’am nikte’, the mu’ujul, and the kaaxan. The ch’a’acháak (“to go through the rain”) is one of the best-known agricultural rites, because it is frequently performed to summon rain. It is a rite that is colorful, emotional, reverent, and communitarian, with an air of spirituality that is not holy but rather a balance between all expressions of life. The tsóol uk’ulil kool is the set of domestic rites performed by the campesino during the growth of the milpa. Finally, there is the tíich’ or bankunaj (“offering”), the most ornate and colorful ritual, which consists of an offering of gratitude that emphasizes coexistence and community, a family celebration for the successful harvest. It implies that the milpa harvest should be sufficient and timely, that one should rest a bit during the day while getting enough sleep at night, and that one should try to share the word and to engage in conversation to inform, educate, and renew memory. These three activities are fundamental for the health of the house and its inhabitants. It is not about healing, but about not getting sick, and the óol4—which is a Yuum iik’—should be in perfect balance with the climate of the house, celebrating the spirituality of health through rites. This is the purpose of the entwinement of time, space, people, and nature itself. If the milpa is healthy it is because time and space are healthy. The sounds and colors will harmonize the melody so that the sowing and harvest will be abundant and festive.

The xook k’iin is woven like a petate mat, but with elements that belong to, or originate in, the casa grande. Others called them “codices,” like those that today, in spite of being Maya, bear names like Dresden, Paris, and Madrid5 (The majority of ancient Maya manuscripts were destroyed by the Spanish colonizers. Of the four Maya manuscripts that still exist today, only one is still in Mexico and the other three are in Europe, where they were renamed after their thieves: Madrid Codex, Dresden Codex and Paris Codex). The codex is like a hammock woven with different types of thread, where we find plants, animals, birds, work, parties, rites, night, day, darkness, light, sounds, colors, rain, drought, cold, heat, dew, smoke, dusk, and dawn. Finally, it is an epistemology with a hermeneutic key for an appropriate reading, which our ancient grandparents called tsolk’iin (ancient Mayan calendar, literal meaning “day count”). It is not possible to separate the beings that give the tsolk’iin life, because it would be like mutilating, hurting, or killing it. The most striking or evident example is the milpa, which binds everything together, and functions as the core of this coded reading, or the key to its interpretation. Maya culture is written or inscribed in the milpa, which is imprinted in nature and interpreted only by those who have been and are part of that rural life due to the emotions and subjectivities created throughout life as one of the threads of the great fabric. Thus, it is not only based on the interpretation of bioindicators. The tsolk’iin is Maya and the xook k’iin is syncretic, ecumenical, pluricultural, and intercultural. The xook k’iin is a window where many cultures of the world meet and share what is fundamental. However, during such archaeological efforts of the word, it is important to reencounter several hermeneutic pieces for a more thorough reading.

Although today it is not an instrument that is generally used, the xook k’iin continues to guide rural communities. It is seen and understood as an interaction of the community with time, and as an experience, or a dance, to the beat of nature’s harmony. The truth is that the xook k’iin has been greatly debilitated by the impact of consumerist and productivist capitalism on the productive activity of the Maya Peninsula, leading to the splintering of many communities into isolated global migrants looking for a Global North where they can fulfill their dreams. The relevance of the xook k’iin on the Yucatán’s Maya Peninsula is linked to the campesinado and campesino communities that continue to practice self-sufficiency—that is, the production of their own food through the milpa. Significant portions of these communities have migrated to the large tourist cities to join the capitalist labor market offered by big hotels, restaurants, or factories that produce mass industrial goods. The productive activity of these proletarians no longer takes into account the xook k’iin and even less the tsolk’iin: the migrant workers are disconnected from the milpa. Thus they begin a process of alienation, until they forget the cry of the ts’uju’uy6 and the colors of the fruits of the ja’abin7, or at least they cease to observe them. For the campesina and milpa communities, the relevance consists of nature’s messages about the potential quality of the current harvest, that is, the ability to see clues in the sounds and colors, in the cold or hot weather, in the morning dew, in the approach and intensity of the rain, or in the afternoon hum of insects. These signs are not only indicated by the weather of the first month of the year but in every hour of every day, week, and month of the year until an abundant harvest is produced, after which the community prepares for the great celebration of the tíich’, the bankunaj, or the “primicia” (first fruits), as it is called in Spanish. In reality, this celebration is not epistemologically equivalent to an act of Christian thanksgiving; rather, it is a celebration of the family meal performed by flesh and blood humans who have transcended matter, as well as by animals, birds, and every living being who tell the tíich’ to those who now inhabit the bolontik’uj8 and ooxlajajuntik’uj9.

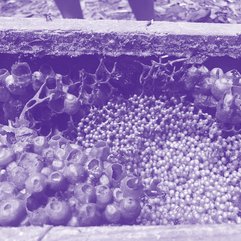

Haizel de la Cruz: "Improntas de la milpa"

Haizel de la Cruz: "Improntas de la milpa"

Although the xook k’iin is a Maya sound, it was probably not known to the Maya people before the conquest. Apparently this name derives from colonial times, since the method of counting the first days of the year as climatic predictors of the remaining months is a system of knowledge in many other world cultures, including those of Europe. This term then seems to be product of a syncretism that was not so relevant to peninsular Maya culture, especially given the brutality of conquest and colonization. An earlier term similar to this syncretic voice is tsolk’iin, a voice supported by ancient writing and the pre-Hispanic Maya calendar. Tsolk’iin is understood as a way of life and not as a method to count the climatic behavior of the year from the days of January, as many seem to believe. It is necessary to delve more deeply into this matter, but the observations of our grandparents reveal the characteristics of a tsolk’iin more than those of a xook k’iin. In any case, the linguistic aspect already shows its reach: the xook k’iin is limited to counting or enumerating, while the tsolk’iin arranges, orders, or rearranges things to create something new. Tsolk’iin is an original system of knowledge, an epistemology of collaborative community work to strengthen the fabric, not only among humans but throughout the Maya casa grande.

Maya culture is a culture of maize that cannot be understood or exist independently from the environment. This is what the Popol Vuj—the ancient words of our grandparents—tells us. But it is also what each campesina experiences and then believes in, and what emerges from her surrounding life. Culture was born from the heart of the milpa, from the forest, from every element and countenance present on earth: water, sky, clouds, wind, rain, dew, sunrise, sunset, night, moon, sun, as well as in each woman, child, and man of the community. It is important to emphasize that the community does not only include humans, but consists of all those who inhabit the house, the casa grande, the peninsular house, the yuukalpeten, as our grandparents apparently called it. One cannot understand the Maya meaning of culture (miatsil or meyajtsil) without including nature and the environment. Moreover, if someone were to question this, it would generate laughter because everyone, starting with children, knows that one cannot exist without the other. Themes such as justice, organization, family, sex, time, the stars, and everything else cannot be understood separately.

In recent years, the xook k’iin, and mainly the tsolk’iin, have been threatened by the implementation of mega development projects such as the monoculture of thousands of hectares of genetically modified soybeans, pig farms, wind and solar farms, high impact real estate tourism, and the misnamed “Tren Maya” (Maya Train). These developmentalist activities have far reaching negative environmental impacts on the communities residing on the peninsular Maya territory. The forest is mortally wounded; in each of the animals, birds, and bees that inhabit it, blood drains into the waters of its cenotes, into the furrows of its milpa. These development projects produce a blackout in the memory, history, and voice of Maya communities. They are barely able to resist enough for the cookstove to keep the last piece of firewood ablaze. What remains is the hope and the light. This fire is their word and it is our voice that today lies among the ashes.

Haizel de la Cruz: "Improntas de la milpa"

Haizel de la Cruz: "Improntas de la milpa"

SUMMARY

The Maya Peninsular of Yucatán is a peculiar observer of the xook k’iin, mainly through its campesinos and campesinas but also through children and communities connected to working the land by means of the milpa. Daily life is an interdependence—or as scholars would say, an intersubjectivity—between Maya communities, weather, and climate, that is, nature. However, today this cultural mode of Maya life is not ascribed to the tsolk’iin. Rather, it is the knowledge and experience of millenary linkage that history has bequeathed to us. The milpa is the primary entity of this cultural segment and its raison d’être, because it is the most relevant activity for the community; it is the source of nourishment, food and drink, health and joy. In short, it is the source of everything that everyone’s life implies. In order to be successful, it is essential that the Maya community form part of the natural fabric as one of the threads of the great web of life conceived through lights, shadows, colors, cold, heat, sounds, forms, and movements, among other expressions of this grand hammock of life. The women and men of the maize affirm that a community is like an ear of maize, and the Maya territory is like the milpa that gives birth to the knowledge and epistemology of life read from the tsolk’iin, or the ecumenical, syncretic xook k’iin that continues to inspire the Yuum iik’ in the casa grande of the Maya people.

One of the powerful reasons for the xook k’iin is health in a general sense, that is, not only corporal but also of the óol, on a personal and community level. If the community is able to link or weave itself between the threads of time and its environment in general, it will be able to achieve the harmony and balance it needs to be satisfied and have the necessary wisdom to successfully resolve physical, emotional, social, spiritual, economic, and other problems that may arise. More than the weather, for the xook k’iin, the climate is the text, the codex, the material for the exegesis. Animals, birds, insects, and fish respond to the stimulus of the charge or energy that each day brings. Just as our mood changes, so does that of each day, which affects the life of everything else. Those who try to understand this from Western epistemology call certain reactions of the environment “bioindicators.” Actually, it is the Yuumtsil that set their clock in motion so that the campesina, after a hermeneutic exercise, can apply it where appropriate.

The peninsular Maya community does not only defend the xook k’iin but the casa grande, the territory, the life of the community. It cannot defend only a part of it, since its environment is the totality of the woven petate mat. If the territory is snatched away and impacted, the voice of the bird is silenced, the light of the firefly is extinguished, and the xunáankab (Melipona bee) loses its sweetness.

Acknowledgement: All pictures on this page were kindly provided by Haizel de la Cruz

Translated by Michele Faguet

1 There is no equivalent in English for this Maya concept. Anthropologists define it as “god,” but this is incorrect. The closest interpretation would be “community father” or “mother of the community.”

2 The milpa is a millennia-old form of agriculture organized around the symbiosis of maize, beans, and squash.

3 Literally “creator,” but in Maya culture this refers to a medicine healer who also celebrates rituals.

4 This concept does not have a unique translation and can be understood in multiple ways according to the context: “energy,” “mood,” and so on.

5 The majority of ancient Maya manuscripts were destroyed by the Spanish colonizers. Of the four Maya manuscripts that still exist today, only one is still in Mexico and the other three are in Europe, where they were renamed after their thieves: Madrid Codex, Dresden Codex and Paris Codex.

6 A thrush-like bird.

7 A tree known in Spanish as barbasco or jabín.

8 Literally “nine worlds.” Others refer to it as the underworld.

9 Literally “thirteen spaces.” It can also be translated as “layers of the sky.”