Yucatán: A Vulnerable Ecosystem

This text is also available in Spanish:

Yucatán: un ecosistema vulnerable entre amenazas y esperanzas

Abstract: This text offers a broad overview of the historical, socio-cultural and environmental context in which some of the main megaprojects threatening the biocultural heritage of the Maya people of Yucatán were developed, among them the Xok k’iin. Yucatán’s ecosystem is susceptible to groundwater contamination as well as the effects of climate change, and these phenomena put the traditional practices and knowledge of the Maya community at risk. Finally, I outline some recent examples of how biocultural heritage has been successfully defended.

The diversity of Yucatan ecosystems

Located on the peninsula that separates the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, Yucatán is one of the thirty-two states of the Estados Unidos Mexicanos (Mexican federal republic) and has a unique ecosystem. Its vegetation encompasses coastal sand dunes, mangroves, tropical deciduous forest, subtropical semi-deciduous forest, seasonal evergreen forest, freshwater swamp forest, savannahs, petenes (small islands covered with vegetation), and hydrophytes. Tropical deciduous and subtropical semi-deciduous forests are the most widespread in the state and are what give the landscape of Yucatán its distinctive appearance. These forests are home to Ceiba aesculifolia and Ceiba pentandra, known simply as ceiba, which have enormous symbolic value for Maya culture, as they represent the connection between the land, the celestial realm, and the underworld.

Yucatán is also considered one of the most emblematic sites of karstic topography on the planet. Most of the state’s soil is limestone, through which water seeps easily, and this has led to the formation of sinkholes filled with water, known locally as cenotes (derived from the Maya word ts’ono’ot, meaning “hole with water”). There are an estimated 7,000 to 8,000 cenotes in the state, though the exact number is unknown. They are the only source of fresh water in the area and are highly susceptible to contamination from sewage and from agricultural and industrial activity.

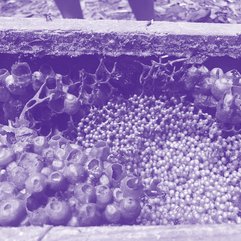

The complex submerged root system of a mangrove forest.

The complex submerged root system of a mangrove forest.As with many communities around the world, the Maya communities of Yucatán believe the forest, mountains (or ka’ax), and cenotes are inhabited by keepers or guardians, including the mischievous aluxo’ob and the more respected balamo’ob. To farm the land or make use of the water, one needs to ask the keepers or guardians for permission, and thank them with the fruits of the harvest.

The impact of colonization

For the Spanish colonizers of the sixteenth century, whose main source of wealth consisted in the exploitation of indigenous Maya labor and the extraction of taxes, the lack of gold and silver in Yucatán was seen as an economic impediment. In his 1542 text Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies), Bartolomé de las Casas described the situation as follows:

now because this region affords no gold; and if it did the inhabitants would soon have wrought away their lives by hard working in the mines, that so he might accumulate gold by their bodies and souls, for which Christ was crucified: for the generality he made slaves of those whose lives he spared.1

Contrasting with the lack of gold, las Casas noted an abundance of

honey and wax, exceeds all the Indian Countries that has hitherto been discovered.2

At present, the Yucatán Peninsula is among the largest producers of honey in the world and exports around ninety percent of the honey produced by Apis mellifera (the European or Western honey bee) kept in Yucatán to the European Union and Saudi Arabia. The honey of the Melipona bees native to Yucatán itself is not exported.

In contrast to the Aztecs in central Mexico, the Yucatec Maya do not have a centralized political structure and are instead organized in cúuchcabalob (provinces). During the colonial period, certain cúuchcabalob made alliances with the Spanish conquistadores, while others resisted. Owing both to this political structure and to the lack of precious metals that would have sparked greater interest for Spanish colonizers, the Spanish conquest of Yucatán was much slower than in other parts of present-day Mexico. Certain historians even argue that it was the Maya who colonized the European conquistadores given that until the latter half of the nineteenth century, it was common for the Spanish in Yucatán to speak the Maya language, eat a Maya diet, and adopt other practices of the Maya culture.3

Despite a strict policy of hispanicization in the twentieth century, the Maya language and culture have adapted and are still very much alive today. Indeed, Yucatán has the second largest indigenous population in Mexico.

The expansion of henequen monocultures

Toward the second half of the nineteenth century, during the era of Mexican independence, cattle, corn, and sugar haciendas owned by the descendants of the Spanish were replaced with the production of henequen (Agave fourcroydes), a plant that flourished in the rocky soil. Henequen fiber was exported to the United States and was used for a variety of purposes, including the manufacture of sacks and ropes for agriculture, as well as to make rope for ships. In 1881, the Yucatán historian Serapio Baqueiro commented that

the entire state is just henequen. Other than henequen, there is nothing at all.4

While more than 35,000 metric tons of henequen fiber were exported in 1888, and exports reached over 200,000 metric tons in 1916. The henequen industry made the hacendada (the owners of the haciendas) into one of the richest classes in Mexico, and they adopted a similar lifestyle to the European bourgeoisie. Their fortunes were based on the exploitation of laborers, who were composed of indigenous Maya as well as Chinese and Korean immigrants, and indigenous Yaqui from the state of Sonora in northern Mexico. Various observers described labor conditions at the time as tantamount to slavery. In 1910, a journalist from the United States named John Kenneth Turner condemned the fact that laborers on haciendas

get no money. They are half starved. They are worked almost to death. They are beaten. […] I heard numerous stories of slaves being beaten to death, but I never heard of an instance in which the murderer was punished, or even arrested.5

Henequen of Yucatan in the period of 1877 to 1959, Pedro Guerra Photography Archive

Henequen of Yucatan in the period of 1877 to 1959, Pedro Guerra Photography ArchiveIn 1847, Maya in eastern Yucatán rebelled in what is known as the Guerra de Castas (Caste War of Yucatán), due in part to the concentration of private land ownership and the persistence of onerous levies such as ecclesiastical fees. During the conflict, indigenous militias took control of the most important cities and towns in eastern and southern Yucatán. Thanks to the support of the Mexican government, the Yucatán army was able to recover the main towns in the region by 1850, while certain localities in the east of the peninsula such as Chan Santa Cruz remained under rebel control until the twentieth century. It is estimated that the population of Yucatán was reduced by almost half due to this conflict: from 505,041 inhabitants in 1846 to approximately 300,000 in 1851. In certain eastern towns like Valladolid and Tizimín, the population declined by even greater proportions.

Pig industry and groundwater contamination

A fall in the production of henequen beginning in 1918 reached its lowest point in 1992 with the retirement of thousands of publicly employed henequen workers. Since the 1980s, however, the federal and regional governments have been attempting to diversify Yucatán’s economy, mainly by way of the maquiladora6 industry, as well as by expanding the deep-sea port of Progreso on the northern coast of Yucatán between 1985 and 1989. This expansion allowed the port to receive greater shipments of grain and facilitated the growth of the poultry and pork industries. Meat production in Yucatán thus doubled between 1984 and 1992, reaching over 38,000 tons in 1993. Since the 1990s, the pork industry has been among the activities to receive the greatest financial support from the Yucatán authorities. At present, the largest producer of pork in Yucatán, Kekén, exports to the United States, Canada, Chile, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and China.

Cenote in Yucatan

Cenote in YucatanAlthough the pig industry and pork exports to North America and East Asia are a source of pride among businesses owners and the authorities in Yucatán, various communities and human rights organizations have condemned the fact that pig farms are contaminating the cenotes, the region’s only source of fresh water. Most large pig farms are located in Anillo de Cenotes, a region made up of fifty-three municipalities in the center and north of the state that contains most of the state’s cenotes. It is also an area for the replenishment, catchment, and discharge of water. Given the importance of the area in terms of water supply, as well as its extreme susceptibility to contamination due to the high permeability of the karst soil, the government of Yucatán established the Reserva Estatal Geohidrológica del Anillo de Cenotes (geohydrological state reserve of cenotes ring) as a Área Natural Protegida (natural protected area) in 2013, although there is still no management program to regulate activities there.

At the same time, pig farmers in the area have decried a lack of access to domestic corn and soybean supplies needed to feed the animals. The Mexican government and the Yucatán authorities have thus also promoted the production of corn and soybean monocultures, including genetically modified soy which is resistant to the glyphosate-based herbicide Roundup. In 2015, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as

probably carcinogenic to humans.7

Agroecological farming in Yucatan

Agroecological farming in YucatanThe impact of industrial agriculture, tourism, and mega-projects

In 2012, the federal government granted Monsanto—acquired by the German multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company Bayer in 2018—a permit for the commercial cultivation of genetically modified (GM) soybeans in seven Mexican states, including Yucatán, over an area of more than 253,000 hectares. In 2016, Yucatán thus became the largest soy-producing region in the country. In September 2011, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that honey approved for human consumption with more than 0.9 percent pollen from transgenic plants must be labeled as containing genetically modified ingredients. The decision affected honey exports from the Yucatán Peninsula to Europe, which prompted beekeepers, honey producers, environmentalists, and human rights advocates to mobilize against the Monsanto permit for the cultivation of GM soybeans. Those opposed to the permit quickly condemned the deforestation caused by soybean monocultures, water contamination due to the use of pesticides, and the death of bees, turkeys, and other animals exposed to toxic substances.

Pig farms and soybean monoculture are not the only activities that cause deforestation and pollute Yucatán’s water. In fact, cattle ranching has been the main cause of deforestation in recent years, especially in the eastern part of the state. According to a 2007 study by the Yucatán government, the area of land under cultivation increased by almost 100 percent between 1976 and 2000. In the same period, Yucatán lost about 30 percent of its forest cover, an average of 23,007 hectares per year. The city of Mérida, considered an oasis of security and tranquility in a country ravaged by violence, has become a central hub for real estate development in Mexico. Over the last few decades, these activities have been carried out on ejido land, which designates communally owned land originally intended for agricultural and other subsistence activities. In the areas surrounding Mérida, this has led to people being dispossessed of their land and to deforestation. Between 1992 and 2019, an area of 192,600 hectares of ejido land on the Yucatán Peninsula was converted into private property through real estate development, cattle ranching, and industrial agriculture.

The enormous scale of tourism as well as the installation of large wind and photovoltaic energy farms in fragile ecosystems have equally contributed to land-grabbing and the loss of rainforest. One of the most worrying projects for environmental experts and human rights defenders alike is the “Tren Maya,” an ongoing federal government project comprising the construction of a railway line stretching over more than 1,500 kilometers—a stretch of which would run over cenotes and caves—as well as the establishment of large urban, commercial, and tourist centers. By March 2022, the project had been the subject of at least twenty-five amparo lawsuits.8

The main complaints have been about the environmental impacts in the region, due to the deforestation of more than 2,500 hectares of rainforest, and the violation of the rights to self-determination, territory, and the FPIC (Free, Prior and Informed Consent) of the Maya communities. The use of the name “Maya” has also been questioned, so it is common for critics to refer to the project as “the train that is not Maya” or

the misnamed Maya Train.9

The climate crisis and the threat of hurricanes and droughts

These socioeconomic processes take place in an environmental context that sees heat waves in the region becoming more intense and lasting for longer periods of time. In 2015, for example, record high temperatures were recorded in Yucatán: 48 degrees Celsius in the municipality of Santa Elena, in the south of the state; and 43.5 degrees in the capital of Mérida. One consequence of these heat waves is the increased severity of forest fires and drought. Experts have also documented the increasingly erratic timing of the wet season in Yucatán, which normally last from June to October. Rainfall is not as consistent as it used to be 10, says Javier Orlando Mijangos Cortés, a specialist in agrobiodiversity and ecological and cultural sustainability at the Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán. Inconsistent rainfall leads to the loss of seeds and constitutes a serious threat for milpa crops. As the Alianza Maya por las Abejas Kabnáalo’on put it:

We are already seeing the effects of climate change: drought and severe rainfall; a loss of forest cover and floral areas that is not only affecting beekeepers, it also has a clear impact on access to water and leads to an increased presence of pests in crops.11

While the geological composition of Yucatán makes it very vulnerable to the contamination of groundwater, its geographical position makes it particularly vulnerable to hurricanes. According to the SEMARNAT–Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources) and the INECC–Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático (National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change), tropical cyclones characterized the most frequent weather-related disasters in Yucatán between 1999 and 2018.

At the same time, several studies have documented the fact that activities such as agriculture and pig, poultry, and cattle factory farming, as well as large-scale tourism and urban development, have contaminated the groundwater of Yucatán’s cenotes. Highly hazardous pesticides have been detected in the water of the cenotes—many of which are prohibited in other countries, such as DDT, heptachlor, lindane, endrin, and glyphosate—at levels above those permitted by national regulations. These pesticides have a negative impact on human health and on the cenote ecosystems, affecting fish populations, for example, as well as birds and bats, both of which are important pollinating species.12

Graphic of the Environmental Justice Atlas

Graphic of the Environmental Justice AtlasMayan defense of the territory

These processes have led to an unprecedented mobilization of Maya communities and civil society organizations in Yucatán. The 2012 fight against the Monsanto permit for genetically modified soy was a watershed event. Since then, beekeepers from the Maya collective Los Chenes residing in the municipality of Hopelchén have managed to convince the Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación (Supreme Court of Justice) to suspend the soybean planting permit, and to force the Mexican government to consult with the affected communities. They also brought international attention to the defense of the bee population, the rainforest, and water. Communities in southern Yucatán and in the municipality of Bacalar, Quintana Roo, have engaged in similar processes of social and legal defense. Despite the prohibition of genetically modified soybean cultivation by Mexico’s highest court, illegal planting persists on the Yucatán Peninsula.

Similarly, 2017 saw the formation of the collective Kanan Ts’ono’ot (“guardians of the cenotes”) in Homún, a municipality located in the water replenishment area of Anillo de Cenotes. Kanan Ts’ono’ot successfully defended ecotourism in the area by campaigning against the threat of contamination from a huge industrial farm of 49,000 pigs belonging to the company Producción Alimentaria Porcícola. Thanks to their intensive political and legal mobilization, activities at the farm were suspended in December 2018.

In January 2018, the Múuch’ Xíinbal, Asamblea de Defensores del Territorio Maya (assembly of Maya territory defenders) was formed. The group has undertaken the community-based and legal defense of the Maya Peoples against the Tren Maya project, the pollution of cenotes, and the construction of huge wind and solar farms that could lead to the deforestation of hundreds of hectares of jungle. Múuch’ Xíinbal has also had important victories in court, including the suspension of renewable energy megafarms and certain sections of Tren Maya.

Although the political and legal mobilization of civil society has been the most visible form of resistance in recent years, diverse conservation practices and seed exchanges have also served to defend the biocultural heritage of Maya communities. This has been carried out, for example, by the seed guardians Káa nán iinájóob (Guardianes de las Semillas Kanan Inajoob) and the Comité de Defensa de Semillas in southern Yucatán. There have also been proposals from the field of agroecology, such as those practiced by the Escuela de Agricultura Ecológica U Yits Ka’an and the social and ecological incubator Cultiva Alternativas de Regeneración, including urban agriculture such as that carried out by the Colectivo Milpa in Mérida. Moreover, beekeeping, milpa cultivation, and firewood collection, among other activities, are practiced by diverse families and communities. These activities are not only productive, they foster a deep knowledge of the environment and the beings that inhabit it. Faced with some of the greatest threats contributing to global warming, the loss of biodiversity, and the pollution of the planet, Maya communities and their allies are fighting back and inspiring hope for a world that is both socially and environmentally more dignified and just.

1 Bartolomé de las Casas, Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552; México: CNCA, 2015), 61–62.

2 De las Casas, 61–62.

3 Nancy Farriss, La sociedad maya bajo el dominio colonial (México: CNCA. 2012).

4 Cited in Gilbert M. Joseph, Revolución desde afuera. Yucatán, México y los Estados Unidos, 1880–1924 (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2010), 55.

5 John Kenneth Turner, Barbarous Mexico (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1910), 22–3.

6 Maquiladoras are manufacturing plants established by foreign companies—mainly from the United States and Canada—that avail of cheap local labor and extremely poor working conditions, in addition to the duty-free and tariff-free import of raw materials, machinery, and equipment. The manufactured goods are then exported to the company’s country of origin.

7 International Agency for Research on Cancer, “IARC Monographs Volume 112: evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides,” World Health Organization, March 20, 2015.

8 In most legal systems of the Spanish-speaking world, the writ of amparo (“writ of protection”; also called recurso de amparo, “appeal for protection,”or juicio de amparo, “judgement for protection”) is a remedy for the protection of constitutional rights, found in certain jurisdictions.The amparo remedy or action is an effective and inexpensive instrument for the protection of individual rights. (Wikipedia)

9 Silvia Ribeiro, “El tren que no es maya,” La Jornada, January 5, 2019; Gloria Muñoz Ramírez, “Los de abajo: El mal llamado Tren Maya,” La Jornada, July 2, 2019.

10 Abraham Bote, “Cambio climático y aumento de población, amenazas para la milpa: experto del CICY,” La Jornada Maya, May 4, 2022.

11 Thelma Gómez Durán, “México: apicultores denuncian avance de la deforestación en la Península de Yucatán,” Mongabay, October 20, 2021.

12 Rodrigo Llanes Salazar and Katia Rejón Márquez, “Agua amenazada: Informe sobre la grave contaminación del Anillo de Cenotes en la Península de Yucatán (México),” Fundación para el Debido Proceso, October 24, 2022.