Making local - Soil & Pigments

Warli artist brothers Mayur and Tushar Vayeda and Maya artist José Chi Dzul, co-developed workshops on natural pigment making, storytelling traditions and environmental guardianship in a series of online working sessions. Over the course of 4 months, the artists and team members of Spore met regularly on Zoom where we discussed the local contexts, challenges and necessities in relation to their respective artistic practices and the community they are rooted in. Some of the leading questions of the conversations were:

- How does the scarcity, lack or abundance of natural material in our surroundings influence our choice of tools, materials and visual languages?

- How do we engage with nature and environmental issues through our art practices?

- In which way and to which extend are our knowledges rooted in the community, how are they created and transmitted? How can we engage with the community, with whom exactly, and why?

- Why is the passing on of knowledge to younger generations important?

- What are the eco-political situations in the different locations, what are the necessities and the local approaches around the issues related to seed, soil, water, land, forest, habitat, life-forms etc.?

- What audiences do we want to reach?

The outcome of these conversations were two five-day workshops that the artists conceptualized, organized and facilitated in their respective local communities in Ganjad and Yucatan in collaboration with Spore Initiative.

The workshop in Dzan, Yucatán took place between the 14th – 18th of November, and in Ganjad from the 6th - 11th of November.

In May 2023 Mayur and Tushar Vayeda will be staying with us at Spore Berlin, continuing the conversation on soil and natural pigments, together with José Chi Dzul who will be joining us also in May/June 2023.

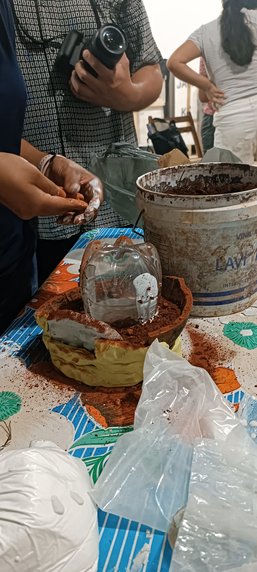

The workshop unfolded over the course of 5 days with a group of 10 children between 11 and 14 years from the community. Together with invited guests and experts, José Chi Dzul introduced the children to different kinds of natural materials, for example plant pigments, honeycombs or soils, that could be used for different forms of artistic expression. The idea was to open up a space for kids to explore processes, materials and tools that – in contrast to industrial products – are part of our natural surrounding and are often connected to daily, sometimes millenary practices. K’aankab, for example, a red soil that is also used to build Maya houses following the milenial construction technique pak’lu’um; or Sascab a thick sand extracted from limestone quarries that has also been used to construct the Sacbés (white paths) connecting the big cities of prehispanic Maya territory. Other materials, such as charcoal are closely connected to the stove in the kitchen, a place of family encounters, of community, and storytelling.

An important aspect of the workshop was also to open up a space for to experience and reflect on local biodiversity, its importance and the challenges it faces. In a visit to the Meliponiculturist collective Flor de Cera, for example, the children learned about the Meliponabee, the tradition of beekeeping, and the properties of its products – honey, pollen, and wax. The latter being also used as binding material for paint. With littered waste, collected in their community, artist Reyes Maldonados created together with the children small sculptures, addressing the problem of pollution in Yucatan, and the influence of human kind on nature.

This text is based on the workshop description of Germán Pech Echeverría and conversations with José Chi Dzul. Part of the workshop were also: Artist and cultural manager Reyes Maldonado; Yeimi Pérez from the Meliponicultura-Collective Flor de Cera.

The five-day Warli workshop with the Vayeda brothers and twelve participants connected young art practitioners of Warli communities in a collaborative space where the elders, researchers, and varied caretakers of the land and environment shared their thoughts on the past and current condition of the century-old artform.

Rajesh Vangad (elder Warli artist) and Shantaram Gorkhana (elder Warli artist and Shaman) shared in their contributions their journey as Warli painters, not only as artists but also as community members and as peoples who have witnessed the changes of environments, materials, techniques and stories. Shantaram also shared from his practice as a Shaman, and its relation to Warli storytelling.

This Indigenous art form, known as Warli, began in Maharashtra and is still widely practised today as one of the oldest artforms and serves as a significant reminder of past methods of land care. The majority of Warli customs and traditions revolve around Mother Nature as the name comes from the word waral – “a portion of tilled land.“

The workshop also introduced the important aspect of storytelling as part of the Warli practice that depicts the current social, cultural, and spiritual life of communal life beyond a mythological perspective. A loose rhythmic pattern is used to create images of humans and animals, celebrations, seasons and scenes from everyday life – visualizing the multiplicity of life in all its varied manifestations. As many local forms of knowledges are not recorded in a written way, as such this is also an important practice of caring by transmitting oral narrations from generation to generation, passing on knowledges and communal experiences, both in social and environmental dimensions.

The workshop also looked into the current challenges evolving around the market conditions. The significance of the art has changed for excessive commercialization, earlier it used to be a social and spiritual tradition and ritual for women and everyday life, now it is a source of livelihood and exploration of individual creativity and a symbol of cultural and artistic pride.

Warli painting has been transferred to paper and canvas since the 1970s. The background of the painting has been changed, transitioning from the mud walls of community houses to paper and fabric especially for global distribution and commercial interest. Also, the medium of the painting changed accordingly from rice paste and bamboo twig to poster color and brush.